I don’t think I ever spoke to G in real life—we went to the same high school, it wasn’t a large one–but I did want to. She was several degrees cooler than me, a kind of emo princess with heavy dark bangs and a sunny disposition. I wore Birkenstocks and men’s shirts from Goodwill over maxi skirts and spent most of my junior year applying to honors colleges. The social canyon between us wasn’t so wide that we didn’t follow each other on LiveJournal.

It would have been roughly 2005. Myspace was the biggest social media network on Earth, but for a kid who was reading Mists of Avalon in the sixth grade, the advent of text-based connectivity was everything. My afternoons after school were spent in front of the shared family PC, AIM messaging friends and crushes and boyfriends and older boys from other schools who bragged about their bands and alluded darkly to their friends' near-overdoses. AOL chatrooms and forums did have the ghoulish older men my parents were worried about, but more interesting to me were the deep archives of urban myths and horror stories, precursors to creepypastas. Literotica offered the thrill of porn without having to load images or video over a dialup connection in an open living room. Livejournal occupied a niche in the online biosphere: it contained my real life friends, and also the rest of the world—but most intriguingly, the people somewhere in between: acquaintances, friends of friends, older kids I'd never interact with.

G often posted cryptically about her crushes and the “currently listening” field in her posts was usually dedicated to Good Charlotte. We didn’t see each other outside of school or even really talk in the halls, but our choice to mutually regard each other online constituted more than knowing of each other. It was my first time with the kind of sideways intimacy that would come to define a certain digital lifestyle: a willingness to be witnessed by (near) strangers in a state of vulnerability we would never risk in person. A direct lineage is formed from the Garbage lyrics we used to post on AIM away messages to cryptic Tumblr posts with dimly-lit digital camera selfies—an urgent desire for our private torments to be seen, but only in peripheral vision.

Members of the digital cohort I came up with are now in positions of middling prestige at leftist digital media platforms or in the amorphous creator economy; I see their bylines and, occasionally, faces at industry events. I've never had a conversation with the vast majority of them, maybe a few Twitter exchanges at most—but I still remember their disastrous early 20s breakups, financial rock bottoms and long dark nights of the soul, chronicled in technicolor on Tumblr and in proto-newsletters, where we followed each other.

Like many people who work in media, I'm watching Twitter (or, X) deteriorate with a mixture of schadenfreude and chagrin. Like many, I'm unimpressed by Bluesky, Threads, Mastodon, or any of the other proposed replacements. I don't want another Twitter, I'm realizing. As the platform grew up, so did a way of being online: my Twitter is linked to my real name, website, newsletter; it’s what I’ve used for years to promote my work and build real relationships. I’m not missing a digital water cooler, but a space to exist as a multifaceted social creature—and I don't know that I want it to be a reflection of my "authentic" self.

Twenty years after I went to high school with G, I live with my best friend, whom I met on Twitter, back when bonds were still formed over baseless shitposting and I didn't have a Substack signup in my bio. I'm in several Discords, but still haven't found a place that lives up to that era—a space where I can function independently from my “real” persona.

Even Tumblr feels too consequential—too many friends had homes there too (or at least art students I had hooked up with in college and now follow on LinkedIn). So, a deeper, more prehistoric form of anonymous blogging, then, a social economy that hinges on handles rather than names and credentials, something I jumped ship on years ago as I worked to build a brand in digital media. I want the satisfying both/and the internet once offered: an audience without the accountability of relationship, connection without real stewardship. A delicate ecosystem unique to the internet of an earlier time.

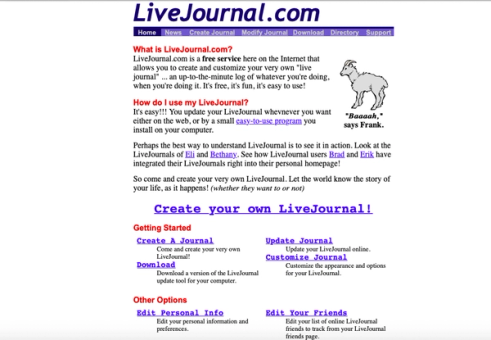

In 1999, an American programmer built custom blogging software to power a site to post updates on his life for his high school friends; six years later, he sold what he'd built to a software company, and a fledgling social media network was born. Like Myspace, it let users post photos and "friend" other users; unlike Myspace, it also encouraged users to share long text posts: an online diary.

This summer, I made an account again—I tried a few versions of my email and password that I thought might date back far enough, but I’d already forgotten my original login; it’s been twenty years. But once there, LiveJournal instantly felt like slipping on noise-canceling headphones in IKEA: an almost somatic relief.

The UI these days is significantly less intuitive than the seamless iOS product flow we're now accustomed to, but even that feels kind of refreshing. I’m struck by the lack of popups or intrusive prompts trying to anticipate where I want to go next. Which means the interface looks a lot like I remember it, but with ugly Google AdSense banners shoehorned in. LiveJournal was sold to a Russian media company in 2007, although the servers remained based in the US until 2016; Russian content restrictions on political and LGBT commentary initiated something of an exodus. Now, a wrong click can detour you into an entirely Cyrillic dashboard without a clear way to navigate back out. Still, much of it feels familiar. Fanfiction-themed challenges coexist with KPop news and digital art journals of painstakingly scanned film photos. Group blogs of daily Christian devotionals compete with posts seeking collaborative writing partners for mpreg erotica. OhNoTheyDidnt is still around, recapping the BET Awards,celebrating a new SHINee video. I discovered an RSS feed where I can still read PostSecret, the anonymous secret-sharing platform based on physical postcards.

A few times, I think I’m wrong, and looking at a cached version of LiveJournal from ten or fifteen years ago. There are complex webs of posts that reference each other obliquely; lists, streams of consciousness, fragmented lines that read like adolescent poetry. It’s all so reminiscent of what my friends and I were doing in our teens—and feels paradigms away from posting a story over eight parts while doing a glowy base routine on TikTok. Then someone references watching Season 2 of The Bear.

Nostalgia aside, LiveJournal is far from thriving; many community blogs show years between posts. “Anybody still out there?” someone asks on a Catholic LiveJournal community in 2017. A few commenters respond to say they’re still around, but the next post on the blog doesn’t come until 2020. Some posts discuss whether they’re ready to move on to spaces like dreamwidth or deadjournal; and yet a core group of users have, so far, chosen to stay.

Tumblr users have worked heroically to find plugins and workarounds for the site’s attempts at introducing algorithmic interventions, working for free to keep the user experience manual and organic. As far as I can tell, LiveJournal has nothing approaching an algorithm. While users can and do embed YouTube videos, the platform is far from video-first. Screenshotted tweets are everywhere, just like they are on every platform, but no one is poaching LiveJournal screenshots to share to Twitter for a hit of weird outré humor. There is no way to share or repost at all; there’s a rudimentary “top posts” and “top blogs” power ranking, which isn’t functional enough for engagement to be a real driving force. No one, as far as I can tell, is making deliberately provocative or misleading posts for clicks.

Despite the Google AdSense presence, LiveJournal profoundly fails to support monetization. A few posters discuss a paid membership, namely that it doesn’t really work. “will I EVER be able to renew my LJ paid account again?” asks a post from September, 2022. It sounds like the payment processor has broken down, and was maybe never fixed; for a while, LJ administrators were giving users a free renewal if they emailed, but it’s not clear whether that policy remains.

Even more notable is the absence of users trying to monetize their own LiveJournal presence—there’s no creator class. In my weeks of casual use, I haven’t seen anyone advertising a small business or its products, or sharing branded service journalism to promote a coaching business or e-books. Is this just because it’s not worth marketing to the digital equivalent of a forgotten city? Does it matter?

It occurs to me that my memories of a better, more human internet—Hossein Derakhshan’s “web we have to save”—dates back to before a critical mass of digital literacy and digital product adoption, before any online space was designed for everyone on earth. So maybe what I really miss is the possibility for true internet subculture, ahistorical digital manifest destiny. Online spaces are designed to expand endlessly and encompass culture at large, and to function as monetarily valuable products. Weird fandom erotica, teenage angst, and longstanding mutual relationships of decades are not, in their organic forms, profitable.

The prevailing opinion seems to be that we’re headed for an era of “group chats and private messaging and forums” now that we’ve reached the end of the useful internet. I’m open to a tentative optimism about what the new paradigm might offer, and also angry about how much we’ve lost to a fetish for capital.

Our anxiety about the current digital moment has shaped itself trying to fix the act of connection, by somehow resetting the ways that we talk to each other online, making them more civil or more humane. This isn't without value, but it's worth remembering that many of my (and our) most formative online experiences weren't solely about forging friendships or inhabiting some kind of Parks & Rec ideal of a town hall.

The internet makes possible a kind of mass parallel play at the game of being human. There are ways of relating to each other besides consuming content or building downlines to monetize our lived experiences. We can still witness each other and be witnessed, if only in the form of posting Current Music: Interpol - "Stella was a diver and she was always down."

Rachel Kincaid is a New England transplant to Minnesota, where she teaches writing and works in newsletters. Her favorite X-Files episode is "Beyond the Sea."