It is the end of the second world war and former Nazi Max is living like a church mouse as the night porter of a luxurious hotel in Vienna. One evening, he is improbably reunited with Lucia, the daughter of a political dissident with whom he engaged in a sadomasochistic relationship at an unnamed concentration camp, now touring Europe with her American husband. After playing coy with each other, Max and Lucia rekindle their love, discarding the trappings of their new lives and surrendering themselves to desire, beginning a slow, deliberate march towards their mutual annihilation.

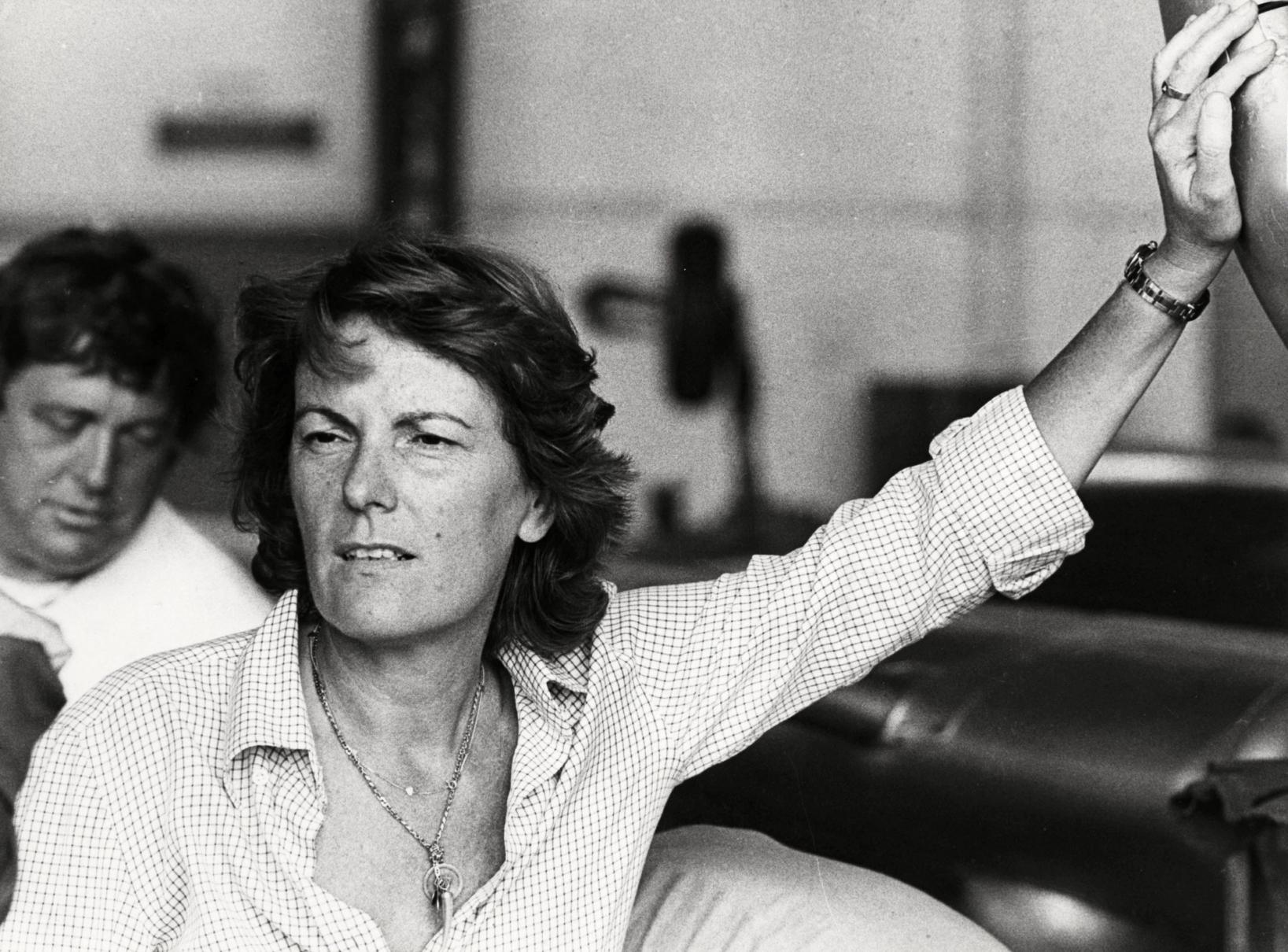

This is the premise of The Night Porter, the fourth theatrical feature by Italian director Liliana Cavani, and the one which has come to define her career. Cavani, 89, is the director of 20 movies with another in production at the time of writing. If there is a subject that she has, in her now six-decade long career, not yet touched, it would be hard to fault her for what could only be considered an accidental omission. Adaptations of, among others, Sophocles (1970’s The Cannibals from his Antigone) and Jun’ichirō Tanizaki (1985’s The Berlin Affair from his novel Quicksand) and no fewer than three films about the life of St. Francis of Assisi (one of which stars Mickey Rourke) can be counted alongside everything from costume dramas to sweeping romances.

This is the career of a hardworking director whose start making documentaries and short films for RAI, Italy’s public broadcaster, would eventually culminate in an estimable body of work. Cavani seems to have the kind of career that would make her the perfect candidate for a so-called ‘rediscovery’ by popular critics or the kind of late-in-life revaluation that Elaine May has recently received. But so far her legacy has been largely defined by The Night Porter.

During its initial release, it was subjected to a torrent of negative reviews from American critics including Roger Ebert, who panned it as “[a movie] as nasty as it is lubricious, a despicable attempt to titillate us by exploiting memories of persecution and suffering” and “as a shallow exploitation of [concentration camp experience], containing no real insight or understanding.” This review also references Susan Sontag’s essay-review “Fascinating Fascism,” where she compares the film negatively—“far less [interesting]”—to Kenneth Anger’s Scorpio Rising and Yukio Mishima’s Confessions of a Mask. This dual characterization of the movie, simultaneously lurid and dull, is one that has followed the movie for some time now.

But contrary to its reputation as a piece of Nazi exploitation, The Night Porter is measured in the treatment of its subject matter, closer, in some respects to Merchant Ivory’s subtle, abnegating examinations of attraction and love. It is a film of nacreous surfaces and dreamy, low-lit interiors. Every frame radiates a cool green light and there is a buttery quality to the deep shadows at their edges. At the same time, it’s directed with an otherworldly sense of restraint. When the two lovers meet again, the camera holds on their faces long enough for a sliver of recognition, a widening eye and a pursing lip are all Cavani shows before the two are separated from each other again. It is one of the most erotic scenes ever put to film and skillfully captures the pain of having to stifle oneself in public. This quality, uninhibited passion observed dispassionately from afar, defines The Night Porter. In her essay “The Bottom of Love,” writer Celeste Marcus defends the film as “one of the great cinematic meditations on love” but it has taken a long time for the film to be considered in this way.

The movie’s best-known scene, in which Lucia wears a pair of suspenders and leather opera gloves as she dances for Max and the other Nazis at the camp, has been assimilated into BDSM culture to the film’s detriment. In context, it is supremely off-putting. Says Marcus: “The scene was not presented to titillate audiences. Interpreting Lucia’s coerced performance as pornographic betrays a lack of decency, of sympathetic imagination, on the part of the viewer. It is not intended to arouse; it is intended to horrify.” The camera is low and moves with serpentine precision as Rampling dances, her ribs visible and mouth contorting around the words to the song as the masked audience stares impassively. It lacks the warmth of the reintroduction scene or the playfulness of one in which Lucia breaks a glass of perfume on Max’s bathroom floor and allows him to crush her hand into it after he takes an initial, painful step into the detritus.

Cavani has been adamant that the story is about the love between Max and Lucia. When pressed on this point in an article about the film’s legacy for The Guardian, Cavani offered a spirited defense of her film:

“There was an attraction which marked Lucia for life…When she and Max meet again, the flame has not faded. She was very young and disoriented by him. She was bowled over. She believed he desired her for who she was. And, despite everything, there was sincerity in his feelings. In its own way, theirs is a romantic relationship.”

The film treats the emotions of its lead characters with purity. Even at the end of the movie, in which they both die, Max and Lucia seem to be entirely at peace with the decisions they made, a sort of moral honesty one couldn’t expect from the type of movie its detractors make it out to be. While a reading of the movie focused on its, admittedly disquieting, surface aesthetics could find little that is sympathetic, burrowing past it reveals one of the oldest truths: that which we love is often that which is most apt to annihilate us. Hesitations and attempts to break the two apart are ignored, unappealing detours from a road which leads to a kind of ideal wholeness the two eventually acquire for themselves. Lucia and Max are, in this sense, a kind of Cathy and Heathcliff emerging from one of the 20th century’s great atrocities, finding solace and a kind of perverse self-identification in the experiences of the other.

Cavani would recapitulate the themes of The Night Porter in her 1981 drama The Skin. Adapted from the book of the same name by Curzio Malaparte, the movie follows the disparate fortunes of the American Fifth Battalion and their Neapolitan hosts as the former begin their advance to Rome at the height of the Second World War. While there is little depiction of combat in the movie, the world of desperation and squalor it portrays is presented with spartan visual clarity, a marked difference from the atmosphere of The Night Porter. Here, the violence that arises from affairs between conquering Americans and their desperate hosts recontextualizes the mythic violence of Lucia and Max’s relationship as one of many atrocities. While it does not defuse the potency of her previous work, it shows that her understanding of Max and Lucia’s relationship is far from naïve and that she is capable of more than her critics have given her credit for.

As I write this, Cavani has finished shooting a new movie, which will be her first theatrical release since an adaptation of Ripley’s Game two decades ago. Based on the physicist Carlo Rovelli’s book The Order of Time, it explores an angle of Cavani’s work that is underdiscussed: her movies about scientists (she has directed television movies about Albert Einstein and Galileo). Having just entered post-production, I hope Cavani has the opportunity to keep making movies for as long as possible and that anglophone audiences will embrace more of her work.

The image from The Night Porter that still lingers with me is from a short sequence at the beginning. Lucia, at an uncertain point in time, is strapped into the chair of a swing ride. Wearing a pink dress and white scarf, her hair kept in place by a thin headband, she gives an elusive smile as the background melts into a deluge of greens and greys behind her as the ride spins. Caught in a moment of perfect ambiguity, the only thing that seems certain is the rider against the tumult. As the film continues to provoke debate, its power—and Cavani’s as well—remains undiminished.

Colin Mylrea lives in Ottawa. His work has been previously published in NY Tyrant and minor literature[s].